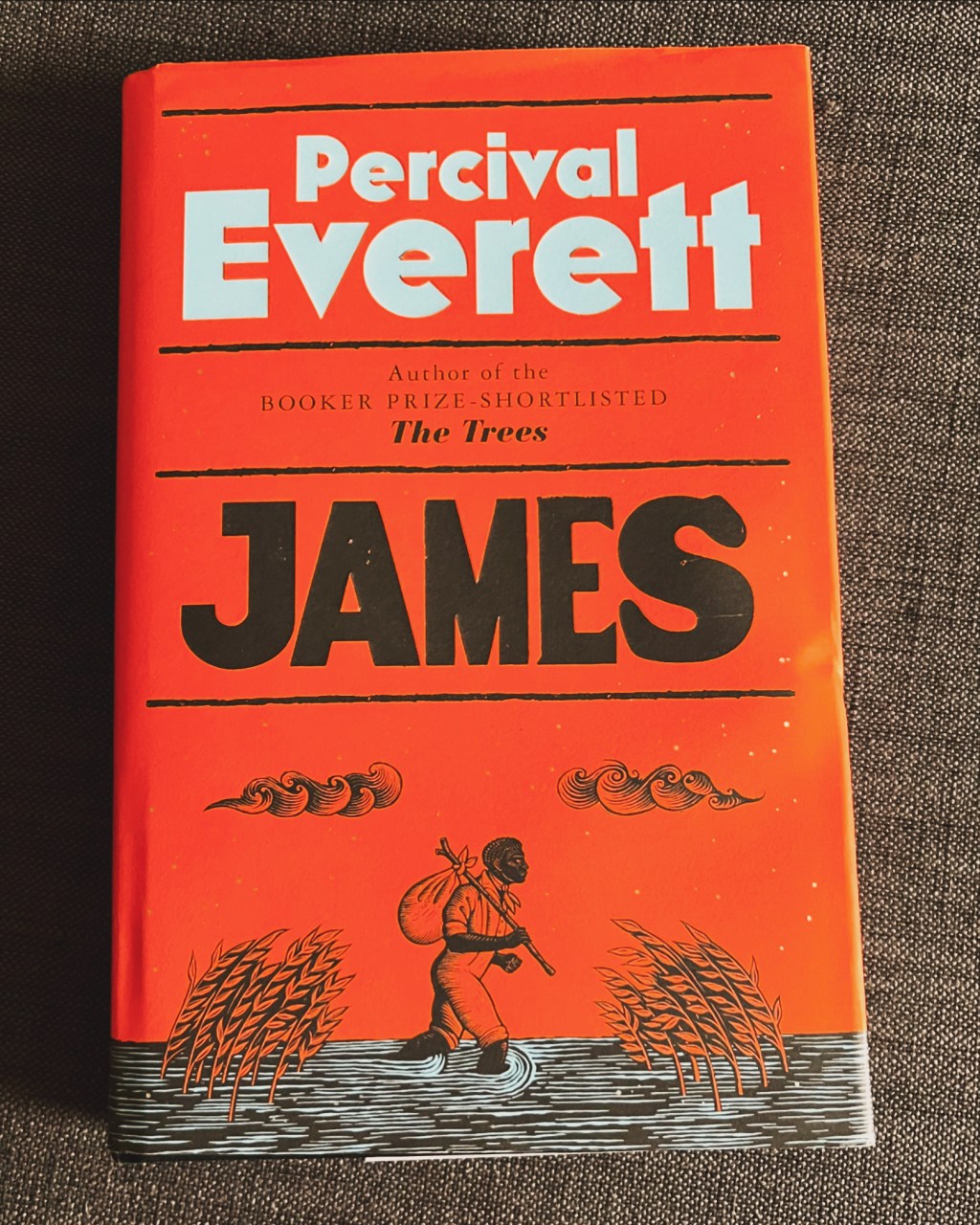

I first heard of Percival Everett when previews started coming out of American Fiction, the film based on Everett’s Erasure. About that time, I also started noticing adverts for James, his new reimagining of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Jim, the enslaved man with whom Finn runs away. Apparently Everett is America’s best kept secret, and his work is only just making its way across the pond. So what was I supposed to do? Not buy it?

Full disclosure: I have never read Huckleberry Finn. This is probably a cultural thing; Mark Twain was never a part of the British education system, at least not when I was in school. We had endless supplies of Shakespeare, poetry anthologies, and the like, but, alas, no Twain. So much to say, I can’t comment much on the intersection between James and Huckleberry Finn.

What I can say is that I thoroughly enjoyed reading this novel. ‘Enjoy’ feels like a strange word to use for a book that focuses on such a dark side of human history, but Everett is clearly a master of his art. The focus on the use of language is excellent. Everett positions well the dichotomy between how enslaved people spoke with each other and how they spoke with the white men and women who purported to own them. In speaking with white people, they protected themselves by attempting to appear as they were perceived—simple, lacking intelligence. But in private, they were truly themselves, discussing life, love, politics, philosophy, and everything in between.

There are some excellent scenes, which have garnered much attention, where James meets with philosophers of old in his dreams. An avid reader, sneaking into his master’s library at night, in states of delirium he discusses the ethics of slavery with several of the European philosophers who had pontificated on the subject. There Everett explores the complexity of the arguments for and against slavery, showing how even those Europeans who were against slavery still had complex and often problematic views. This kind of sequence could have been gimmicky, but Everett pulls it off well. He never lingers too long, and doesn’t lean into it too hard, which is to the book’s benefit.

Though, confessedly, I don’t know Huckleberry Finn well, where I understand James diverges from its source material is where I think it is at its strongest. There are times where Finn and James are separated, and this gives Everett the freedom to explore more deeply the themes of justice and the experience of enslavement.

Overall, I rate this book very highly. It tackles a difficult topic in a novel and compelling way; and those who read Huckleberry Finn at school would do well to read this as a companion.